Serpentarium

Our museum quality Serpentarium exhibits 30 of the most beautiful and deadly snakes of Costa Rica. The exhibition puts you face to face with such famous snakes as the Bushmaster, Terciopelo, Green Vinesnake, and Golden Eyelash Viper to name just a few.

Below are some of the snakes you will find in our Serpentarium:

English Common Name

Scientific Name

Spanish Common Name

English Common Name

Scientific Name

Scientific Name

Spanish Common Name

English Common Name

ScientificName

Scientific Name

Spanish Common Name

Snakes in Costa Rica

There are 137 Species of Snakes in Costa Rica. There are 22 Venomous Species in Costa Rica, mostly from the Viper family with a few Coral Snakes and the Sea Snake from the Elapid family. 92% of the Snakes in Costa Rica exist between sea level and 4,900 feet (1,500 meters) in altitude, primarily in the Tropical and Subtropical Forests. Only 8% of Snakes in Costa Rica exist above 4,900 feet (about 1,500 meters) in altitude. The altitude of Waterfall Gardens ranges from 4,200 to 5,225 feet (1,300 to 1,600 meters).

There are 15 Species of Venomous Snakes on the Pacific side of the country and only 9 Species of Venomous Snakes on the Caribbean side. For 25 Species of Snakes in Costa Rica, this is the southern limit of their existence. For 30 Species of Snakes in Costa Rica, this is the northern limit of their existence. With 55 Species having their northern and southern limits in Costa Rica, it gives testament to Costa Rica being the “Landbridge of the Americas” where Species from North and South America meet. There are 13 Species found only in Costa Rica (and its close neighbors).

Although the Neotropical Rattlesnake and the Bushmaster have more powerful Venom, the most dangerous Snake in Costa Rica is the Terciopelo or Fer de Lance Pit Viper. They are more dangerous because they live in areas closer to human habitation and reproduce in enormous quantities (Litters with up to 90 offspring!) Terciopelos are located in all areas of Costa Rica except the very high mountains.

Sea Snakes live in the waters off the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica (not along the beaches). Although feared for their extremely potent neurotoxic venom, the Sea Snake has very limited ability to bite a human because of its small mouth and rear fangs. Even if one did manage to bite you, there is an 80% chance that this would be a “Dry” bite with no venom introduced.

Facts about snakes

Facts about venomous snakebites

Antivenom

There are two types of Antivenom used in Costa Rica. One is for all Bites from the Viper family and one is for all Bites from the Elapid family, this includes Coral Snakes and Sea Snakes.

The Antivenom is made from injecting small quantities of Venom into horses and allowing their blood to build antibodies to combat the Venom. Their blood is then taken and separated into a serum containing the antibodies. A small amount of this serum is tested on the person before administering a full dose to make sure there is no allergic reaction. If no reaction, the proper dosage is then assessed depending on the severity of the bite.

CAUTION: Administering Antivenom to a person allergic to the horse serum can cause a severe anaphylactic shock that is more dangerous than the Venom itself!

How to Avoid Snakebites in Costa Rica—Safety Tips for Avoiding Poisonous Snakes in Costa Rica

Do not travel on unlit paths at night without a flashlight. Most venomous snakes are active at night and at dusk. Always watch where you step.

Exercise caution when exploring – avoid passing through heavy brush or hollow logs without first investigating thoroughly. Do not stick your hands in rock crevices or pick flowers or other plants without first investigating the area around them for a sleeping snake.

Be sure to wear proper foot gear – hiking or heavy walking shoes – do not go barefooted or wear sandals to go exploring in high grass or brush.

Do not place your sleeping bag(s) next to brush, tall grass, large boulders or trees where snakes are known to live and nest. Place your camp site and tents in a cleared area and use mosquito netting tucked well under the bag to provide a barrier.

Do not try to pick up snakes or handle them unless you have formal training and are able to handle them efficiently. Most experts advise against trying to handle even a freshly killed snakes as their nervous system may be still active and they can still deliver a bite!

Serpentarium

CONSTRICTOR FAMILY (BOIDAE)

Appeared 65 Million Years Ago

These nonvenomous snakes are the oldest and largest members of the snake family still existing on the planet. They were the dominant family of snakes from 65-36 million years ago before the more evolved Colubrid family appeared and began to compete with them. Because they existed before many of the landmasses separated they have a worldwide distribution. Boa constrictors exist predominantly in the tropical Americas and pythons, their close relatives, evolved in the regions of Africa, Asia, and Australia. Their Primitive features include a lack of venom, a rigid jaw, heavy skull, pelvic bone structures, and the remains of vestigial limbs in the form of spurs or claws inherited from their lizard ancestors.

Evolutionary Adaptations

Some species of constrictors show an evolved adaptation in the form of heat sensitive scales around their mouths. Although similar in function to heat pits on pit vipers, this physiological characteristic evolved separately and is not nearly as effective as the pit viper’s heat detection capability.

Hunting

Their hunting technique is characterized by a “lie and wait” ambush style as is true with most snakes that consume small mammals that are faster with more long range endurance than them. Their color pattern is ideal camouflage especially during nocturnal hunting. To catch prey a constrictor retracts its head and strikes the prey hard wrapping its body around for constriction. They do not crush their prey but rather suffocate it by gradually tightening their grip each time their prey exhales. Death occurs from lack of oxygen or because the heart cannot pump blood through the vascular system. Some arboreal constrictors have special teeth that allow them to strike and hold moving prey such as birds or bats. Without fail the constrictors always consume their prey head first. These snakes prefer a diet of mammals and birds because constriction is more effective on warm blooded animals that need to breathe more frequently. One of the primary differences between Boas and Pythons is their manner of reproduction. Boas bear live young (viviparous) while Pythons lay large quantities of eggs (oviparous) and protect them during incubation. The python is one of the few snakes that demonstrates parental care.

COLUBRID FAMILY (COLUBRIDAE)

Appeared 36 Million Years Ago

It is currently the dominant family of snakes on all the world’s continents except Australia. In Costa Rica this family represents 104 of the 137 species. They are found in trees, on the ground, underground and in the water. The most commonly recognized species are the garter, grass, rat, and whip snakes.

Evolutionary Adaptations

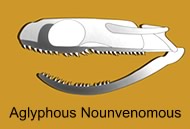

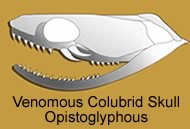

Rear Fangs and the First Venom

Although two thirds of these snakes are completely nonvenomous the other one third evolved the first rudimentary venom produced by an organ in the head known as Duvernoy’s Gland. As a component of this adaptation came a primitive venom delivery system in the form of solid rear fangs and later, grooved rear fangs. Although effective on their prey the Colubrid venom is weak and their rear fangs very inefficient from a defensive standpoint. Because of this the Colubrids represent little danger to humans. However, their venom can cause localized symptoms in humans including pain, swelling and continuous bleeding. Almost all of the Colubrids harbor bacteria in their mouths that can cause infections if a bite wound is not properly cleaned. BEWARE-Venomous Colubrids are often listed as nonvenomous in many of the snake guides- the best advice is not to attempt to handle or capture any snake in the wild.

Hunting

The venomous species hold on to their prey and allow the venom to take effect. The nonvenomous species may use constriction like the boas, or immobilize their prey by thrashing, or by the sheer force of their strike. Camouflage and stealth also play an important part in capturing prey.

Antipredatory Traits and Behaviors

The Colubrids have evolved a few sophisticated antipredatory characteristics that aid in their survival. Some species voluntarily break their tails, which keep moving, to distract an oncoming predator while escaping. A few others feign death by rolling over and exposing their stomachs. One of the most effective antipredatory trait is mimicking the color patterns and markings of the venomous Elapid and Viper species like this Milksnake from the Colubrid Family.

ELAPID FAMILY (ELAPIDAE))

Appeared 22 Million Years Ago

Although the family accounts for only 10% of the world’s snake species their members are the most deadly and include the Cobras, Mambas, Coralsnakes and Seasnakes. They are the dominant family of snakes in Australia and therefore are thought to have evolved about 22 million years ago just prior to the continent of Australia breaking off from the great landmass of Pangaea.

Evolutionary Adaptations

Front Fangs

These were the first species to evolve front fangs and powerful neurotoxic venom. In the more primitive species of elapids venom is conducted through grooves in the front fangs and in the more evolved species the fangs have an internal canal to conduct venom. The advantage of front fangs is the ability to inject venom with a quick strike and then release the prey to allow the venom to work without risking injury to themselves while the prey struggles.

Neurotoxic Venom

The venom travels from the bite wound to the bloodstream and within two to six hours begins blocking neurological transmissions leading to progressive paralysis of certain muscle tissues. Symptoms include loss of muscular function, heavy salivary secretion, headache and in severe cases cardiorespiratory collapse. The victim needs to be treated with a specific antivenom designed for a Coralsnake or Seasnake bite. Some Elapids also have hematoxins (like the Vipers) in their venom that attack and kill red blood cells and muscle tissue and begin to externally digest the prey. In Costa Rica there are only six species of Elapids with five species represented from the Coralsnake genus and one from the subfamily of Seasnakes. Although highly venomous these snakes represent 5% or less of the total number of annual snakebites in Costa Rica. Approximately 50% of Coralsnake bites are “Dry” bites where no venom is injected. The Coralsnakes and Seasnakes have bold color markings to advertise to predators, especially birds, their lethal nature. For this reason there are eleven Colubrid species which mimic the color pattern and share the protection of the Coralsnake markings.

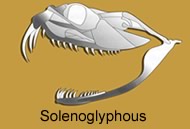

VIPER FAMILY (VIPERIDAE)

Appeared 20 Million Years Ago

The members of the Viper family are the most advanced of all snakes from an evolutionary standpoint. They can survive in extreme climates ranging from the Arctic Circle to the hottest deserts and at the highest altitudes. They are not found in Australia and so are thought to have evolved after the continent separated from the major landmass Pangaea around 20 million years ago. Most vipers have short stocky bodies and cannot chase down prey. They employ an ambush strategy of lying motionless in the night awaiting small mammals to cross their path. This behavior consumes less energy so they can feed less often and reduces the chance of being exposed to a predator while traveling.

Evolutionary Adaptations

Hinged Front Fangs

The viper’s fangs are improved over that of the Elapids because they are longer and therefore can inject venom deeper into the tissue of prey. They are able to manage these long fangs because they are hinged and can be folded up into the roof of the mouth when not in use but deployed forward quickly for a strike. They are hollow and connected directly to the venom glands so they can inject large quantities of venom rapidly..

Improved Venom

Viper venom is a hematoxin comprised of over 20 digestive enzymes combined with various other toxic components that when combined yield a destructive effect on red blood cells and muscle tissues. The venom is the first phase in the digestive process and softens or breaks down the proteins and lipids of the prey to ease in the swallowing process. This destructive venom aids the snake’s digestive process especially in cold climates. The more venomous snakes such as the Bushmaster, Terciopelo and Neotropical Rattlesnake also have neurotoxins in their venom similar to the Elapids.

Heat Detection Ability of the Pitviper

These snakes have heat pits located on each side of their face that contain ultrasensitive thermoreceptor cells able to detect changes in temperature of less than .002 degrees Farenheit. They use the two heat pits like binocular vision to triangulate range and distance to their prey in complete darkness. Studies show they rely almost exclusively on this sense and not on eyesight to hunt for prey.